| |

|

MAKING RECORDS WITH ROBERT POLLARD (both together and apart)

By Todd Tobias

|

Chapters

|

INTRODUCTION

I'd like to take a look back on the albums I produced for Robert Pollard between 2004 and 2015. A version of this essay was originally shared with visitors to the 2019 Sunday night listening parties organized by Jeremy St James. For those whose interest goes deeper than an enjoyable listen, I hope I can add something to the picture. I have no insight into Bob's songwriting or artwork. And since I worked alone most of the time, I have no funny anecdotes to share about studio high jinx or magical moments of artistic brilliance. These are personal impressions and a few technical notes about my work on the albums, and nothing more.

While listening again to these songs, I sometimes receive flashbacks of random, peripheral happenings to the recording process. There was the day during my work on Coast To Coast Carpet Of Love, when my wife Carla came to pick me up at the studio because my car was at the mechanic's. I told her to please take a seat because I needed about 20 more minutes to nail down a guitar track. After sitting quietly and listening to me play the same guitar passage over and over and over, Carla looked at me bewildered and asked, "What are you doing?" She had a vague idea of what I did but she'd never seen me in the studio doing it. To her it looked a bit mad. Looking at myself through her eyes made me think "Yes, this is a bit mad, isn't it?

"Right now I'm the guitar player," I told Carla. "A couple of weeks ago I was the drummer. Next week I'll be the bass player. But I'm not the singer. He'll be coming next month."

Some would say this is not the proper way to make rock and roll. Without a band playing together, how is it possible for each player to feed off the energy of every other player? It's a good question. To a listener who is unable to peek behind the curtain, does it matter how a song is put together?

I don't know. I guess it's up to the listener. If people dig it, then maybe it doesn't matter. To Bob it didn't matter - at least some of the time. For a while I suffered while second guessing myself over the basic question of whether or not I could pull off being a "band." Eventually I quit asking the question because Bob seemed happy with my work. That was all that mattered. With Bob happy I could put my mind at rest. As to what his fans thought of my work, I didn't have a clue. I doubt if they gave it much thought.

In 2001 at the age of 34 I began working as a sound engineer/producer/performer with Bob and my brother Tim on the rough and ragged debut album by Circus Devils. From there Bob asked me to co-produce GBV's Universal Truths And Cycles, Earthquake Glue and Half Smiles OF The Decomposed - a huge leap for me at that time.

At the mixing desk with GBV, listening to a playback at Cro-Magnon Studio in Dayton during the Earthquake Glue session.

The band from left to right: Bob, Nate, Kevin, Tim and Doug. Todd is seated at the mixing desk. (photo by Matt Davis)

After working with the band and finishing a couple more Circus Devils albums with Bob and my brother Tim, Bob asked me to take over the music recording on his 2004 solo album Fiction Man. This felt like another big leap. As before I was glad for the new challenge and grateful to Bob for his faith in my abilities. I assumed that based on some of my Circus Devils work, Bob had the idea that I could handle all the band duties for his new album on my own. After I passed the audition on Fiction Man, we went on to make 16 more of Bob's solo albums and 3 EPs.

Besides being the best songwriter I'll ever have the privilege to work with, Bob is also the funniest person I've known. I always enjoyed his visits when he made the trip up from Dayton to record his vocals or lay down guitar tracks. He was always full of enthusiasm for the project of the moment, and his enthusiasm was contagious. I'm not much of a talker so I enjoyed listening to him tell stories, or talk about what he'd been up to, or deliver reports from the world of GBV.

The musical bond Bob and I share defies explanation so I won't try to explain it. Something clicked - a kind of unconscious sympathy - that allowed us to get on with making records together without having to talk much about it. That isn't to say there was no communication in the pre-production stage. I would ask questions and propose ideas and Bob would give instruction based on his vision for a song.

Much of the time it was understood what a song needed, but Bob made sure to remind me to "make it kick ass" or "add strings to make it pretty." A couple of times Bob referenced the work of other artists (The Who and John Lennon are two that I recall). But for the most part it was a matter of living with Bob's demos for a few days and letting the songs sink in before knuckling down and getting on with building the finished music tracks.

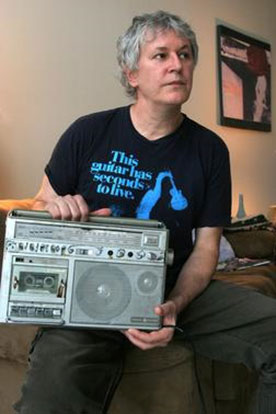

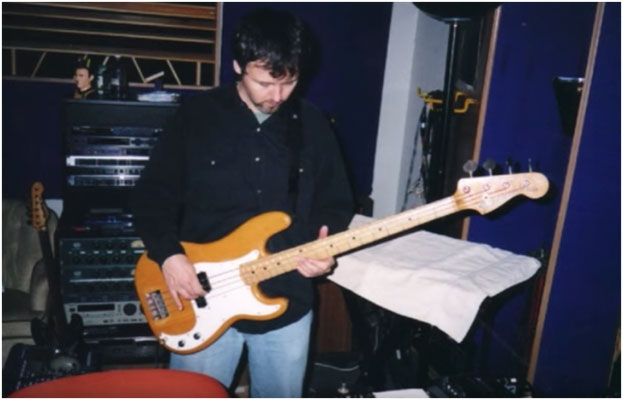

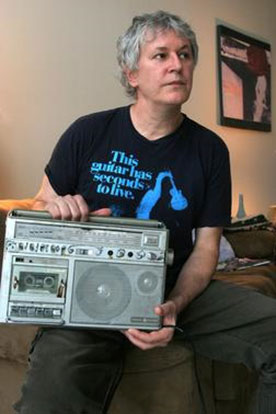

Bob's demo workhorse was his portable mono cassette machine. On each demo recording Bob accompanied himself on acoustic guitar.

Bob with his long-time songwriting partner

(photo by Rich Turiel)

Often Bob brought the silver boombox with him to a vocal session, which allowed him to reference vocal lines directly from the cassette demo. If a demo recording seemed complete, then it went straight to the album as is. 'Losing Usage,' 'Come Here Beautiful,' and 'Wild Girl,' are a few examples. Bob's demos can also be heard on the Psycho and the Birds records - serving as the basic building blocks on every song.

My job was to come up with the accompaniment to Bob's main guitar - a process involving a number of stages. For the albums From A Compound Eye and Normal Happiness, things were made simpler by the fact that Bob and I performed the initial basic tracks together (Bob on guitar and me on drums). But for the other thirteen or so Robert Pollard solo albums and Eps I worked on, we did not perform together as a tracking unit. I would begin, either with Bob's cassette demo, or with his main guitar track as my primary reference. Using a 4-track cassette recorder, I began by making my own demos, adding in secondary guitar parts and bass guitar. Next, I'd sit down at the drum kit and work through drum patterns while monitoring my 4-track demos through headphones.

Gradually each song would lodge itself in my mind, becoming ingrained enough to allow me to "be" each member of Bob's back-up band. This is important to mention, because I couldn't be the drummer or play anything else until the song came alive inside my head. It was not just a matter of memorizing patterns. Each song was like a painting inside a gallery. In some cases a song could be a little world unto itself. I did my best to find myself inside that world, and not simply be a technician providing serviceable backup.

Once some measure of familiarity was established with a song, I could slip in and out of it without trouble. I could build it up from scratch if necessary. Most important was the ability to add drums without thinking. When it comes to drumming, thinking is the enemy. As soon as the songs were incorporated into my nervous system, I was ready to begin recording - adding one instrument at a time while being my own sound engineer.

Once the song's basic building blocks were in place, I could add in the extras (keyboards, homemade samples and percussion). The next stage was creating a stereo instrumental mix, which I would send off to Bob. This was the part I think Bob enjoyed best - getting the music mixes and hearing for the first time how the finished songs would sound behind his vocals. It was then time for Bob to come up to the studio and lay down his final vocals. Gradually, step by step, I witnessed each song come alive, and shared in Bob's excitement at the vocal recording sessions. Saying it was magical will seem cliché, but that's how it felt much of the time. Next came the vocal mixing, and finally, the songs were sent off for mastering.

Each year there would be a Robert Pollard solo album, or sometimes two. In between I'd be working on Circus Devils music. Thrown in to the mix were three records from Psycho and the Birds. For about 15 years it was like that - no time for rest or to reflect on or celebrate what was happening - just being in the thick of the music. Sometimes it felt like being at sea with Captain Pollard on a years-long voyage to parts unknown.

If I had a problem with being the producer on Bob's solo albums, it was never on account of the oblique character of the material. I usually get along with anything that's uncanny or strange. The problem was coming to grips with the basic idea that I could take charge of Bob's songs and give shape to them. The responsibility of it seemed outrageous, at least at the beginning.

Was I right to be fearful? Looking back, I regret that I had this fear - a fear that I might fail to do right by the songs, or even to ruin them. The fear made me hold back and doubt myself. Sometimes it made me act conservatively when I should have said "to hell with it" and pushed things into a different space. There was always the temptation to make things more my own. You can hear this on Fiction Man. From the very first song, 'Run Son Run,' I seem to be taking charge of the music in a presumptuous way. When I look back I feel that I had to do it that way in order to establish a line in the sand - not with Bob but with myself. If I stepped too far I had to see exactly where that step landed. I had to calibrate myself to stay on the safe side of that line. After Fiction Man I remained on the safe side for the most part, at least where Bob's solo albums were concerned. With Circus Devils and Psycho and the Birds there was little holding back. I tend to think it was a good thing to be cautious with Bob's albums, but on the other hand, there were times when my fear of making things too "weird" kept me inside the box when I might have been more adventurous. Charges of "lackluster production" are probably deserved.

Thankfully the quality of Bob's songwriting transcends the musical treatment of his songs. Because of that fact I don't worry that something I did, or failed to do, might have ruined a song. But at the beginning when I first started working on Bob's albums, I did worry about it. I should have known that no matter what form the musical accompaniment might take, Bob would always manage to shine through loud and clear.

I always appreciated the fact that a close examination of Bob's work will not allow you to pin it down. But there is enjoyment in not pinning it down. I believe the organic elusiveness of the songs is one reason Bob's work will endure. I feel lucky to have been a part of that adventure and I thank Bob for bringing me aboard and awarding me with his trust.

You will find some studio-related minutia here that will likely be of little interest to those who don't mess around with audio gear and instruments. Hopefully there's enough other stuff mixed in for the rest of you to enjoy. I'd like to thank everyone who attended the 2019 online listening parties for all the appreciation they expressed for me and my work. Revisiting these albums with you all has been gratifying and humbling.

Bob and Todd in the control room at Waterloo Sound in Kent, Ohio during the Half Smiles of the Decomposed session (2004).

(photo by Rich Turiel)

Back to top

|

FICTION MAN (2004)

I would eventually get used to taking on a project like Fiction Man, where I took Bob's acoustic guitar demos and used them as a blueprint to build finished instrumental tracks. But Fiction Man marked the first time Bob asked me to do it.

There is a primitive and playful quality to Fiction Man that wasn't to be repeated in just the same way, especially when it came to the production. This is an album where the "muchness" in the treatments is sometimes too much. This is interesting to me because at that time I was recording on only 8 tracks. In light of the work on all the subsequent albums, where 24 tracks were used, having a limitation like 8 tracks helped to make me more resourceful.

Bob's demos for Fiction Man were leftovers from Guided By Voices' Earthquake Glue, but the songs did not sound to me like table scraps. These were songs I could sink my teeth into. The playful exuberance in Bob's songwriting helped me to put my nervousness aside and simply enjoy myself. Once the songs sank in, I was able to lose myself in the work and forget that I was ever skittish about taking over the musical accompaniment. At that moment in time, if Bob had given me the demos for From A Compound Eye, let's say, then I might have freaked out on my first time at bat. But the small-scale vignettes of Fiction Man were just the right size and scope for me to handle at that time.

I brought my Fostex 8-track reel tape machine to Waterloo Sound; the home studio owned by Scott Bennett in Kent, Ohio where I'd already done work with Bob and GBV. Scott was kind enough to allow me to do my tracking for Fiction Man there. After the completion of this album I'd be recording non-stop at Waterloo Sound until 2009, when I moved the studio to my basement.

When I mention song treatments being "too much," it's mostly on account of the noisy elements - those weird homemade samples of the sort used on the Circus Devils records. I think the song on which the controlled chaos is most effective is the one I already mentioned - the opening track 'Run Son Run.' This was also the very first song I tackled. The result gave me confidence as I moved on to the other tracks.

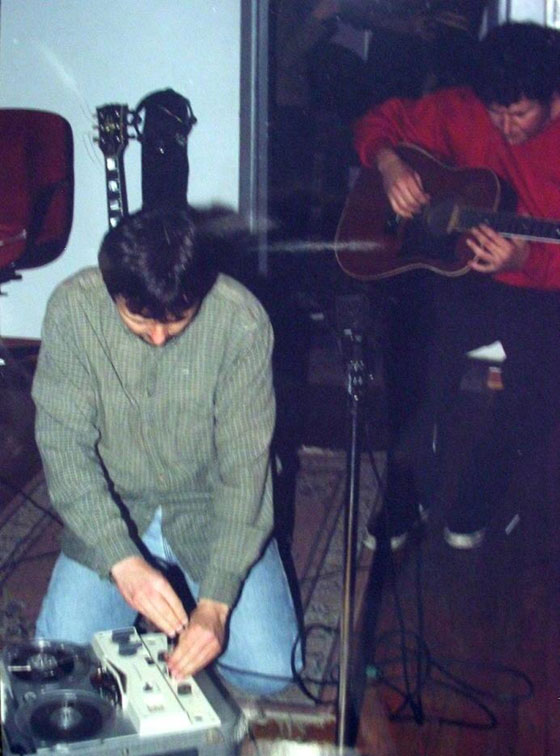

One tool that helped me deal with the 8-track limitation was an old Webcor tube-driven, single-track tape machine. When I overloaded the microphone signal on the Webcor's input, the result was the kind of nasty and sweet sound you sometimes hear on 1960's-era garage band recordings. This is due to the old-time machinery and vacuum tubes hidden in the guts of the mono tape machine, causing a very specific type of tape compression.

If I set up a single microphone about 5 feet directly in front of the drum kit at chest level, I got a pretty good sound using the Webcor machine.

The old mono (single-track) Webcor tape recorder. With no VU meter to monitor the input levels, I always ended up overdriving the signal (causing a pleasant tube distortion). Some examples of the "Webcor Sound" include the drums on 'Run Son Run,' 'Louis Armstrong Of Rock and Roll,' 'Their Biggest Win.' 'Paradise Style,' and later on, 'The Killers' (both versions). Another Webcor track is 'Cock of The Rainbow' from the 'From A Compound Eye' album (vocal and guitar both picked up on a single microphone)

The problem with recording a stand-alone drum track on a mono machine was having no foundational music tracks to play along with. In other words, when I sat down at the drum set, I had no guitar or vocal or anything else to listen to and play along with. It's an example of the importance of having the finished song firmly lodged in my brain before I sit down to play.

With the single Webcor drum track bounced over to the 8-track machine, I had 7 available tracks to fill, minus one or two tracks set aside for the vocals. Sometimes I had to use up an additional track for a kick drum overdub - this whenever the kick drum on the Webcor track got buried once the guitars were added in. On the more aggressive songs it meant only 6 tracks left for instruments and vocals (including the all-important guitars). So every track had to count. It also meant there would be little room for subtlety.

The insistent, manic quality of 'I Expect A Kill,' comes from reproducing Bob's original single-string guitar part from the demo using a parallel combination of electric guitar, high-attack keyboard notes and vocal samples of chanting natives all synched together rhythmically. Part of the percussion backing was achieved by smacking two big stones together and distorting the sound. I know this sounds very cute, but what mattered was the sonic result, which I enjoyed. In those days I was still new to recording, so experimenting in this way was always charged with excitement.

On 'Losing Usage' we hear Bob's original double-tracked demo which captures a composition and performance going on simultaneously as Bob weaves together the vocals and guitar. This was not the sort of song that could be replicated or improved in any way by recording it again, so the original was used.

Chris Sheehan appears as a guest musician for the first time on a Pollard album, adding an elegant touch of piano on 'Conspiracy Of Owls.'

It was fun to change up the approach and give each song its own flavor. On 'Built To Improve' it sounds as if Bob is backed up by a band of ogres. On the spazzy 'Trial Of Affliction And Light Sleeping' it's more like a band of crazed monkeys.

As with 'Trial of Affliction,' Bob's lyrics on 'It's Only Natural' also contain a theme of angst connected to his humor-tempered dismay over the changes going on in our world. That was 17 years ago as I write this. Now I almost feel nostalgic for that dismay seeing as willful ignorance has become institutionalized. As Bob observes; "I can take a garden and turn it into a grave. It's only natural."

My personal favorites on Fiction Man are the pretty songs ('Children Come On,' 'Sea Of Dead,' 'Conspiracy Of Owls,' 'Every Word In The World' and 'Night Of The Golden Underground'). I was glad for the chance to change up my approach and show Bob that I could do more than Circus Devils-style freak rock. It may have been a leap of faith on Bob's part to hand over those pretty songs to me. 'Every Word In The World' is one of those songs of Bob's that gets to me thanks to his poignant melody. 'Night Of The Golden Underground' is another low-key beauty.

Fiction Man marked my discovery of the farfisa organ. As Simon Workman has observed, the farfisa became my go-to keyboard on future albums. I also used the Mellotron flute a lot and other flutey sounds in the arrangements. Bob always requested "strings," which I could sometimes pull off using my Ensoniq ASR-10 sampling keyboard. When I couldn't pull it off, we had Chris George; our go-to cellist on call to provide bona fide strings.

Coming back to the 8-track tape machine used to record Fiction Man, I'd been using it for other albums including Pinball Mars and Five. Looking back, I especially like the work I did on that machine. In later years I'd sometimes get nostalgic for the primitive set up I had with the ¼-inch tape reels, portable ART preamps and radio shack microphones. Later on, when I was able to collect some better gear, some of the charm was lost. Having 24 digital tracks was liberating, but having my hands in the mechanical-workings of the tape machine, for example, made me feel more involved and more a part of the songs somehow. Analog recording in general always feels more real to me, probably because it is. Playing a guitar track and then stopping the tape to rewind and play it back again had a psychological effect of some kind that helped me to feel that I was somehow inside the music. Something of that feeling was lost when I began using the 24-track hard drive digital recorder. I wasn't done with tape recording, however. Scott Bennett had a two-inch tape machine with 24 tracks that survived for two of Bob's upcoming solo projects. I also returned to the 8-track now and then, mostly for Circus Devils.

I mixed Fiction Man at home on my 8-channel mixer and monitored the mixing through a little boom box, just as I'd done while mixing Ringworm Interiors, Pinball Mars and Five. I like to mix on boombox speakers because they tend to reveal how different musical elements sit with each other. Once the bass guitar was added as the final step, I would then switch to headphones and my car stereo to see how things were shaping up on the low end of the EQ spectrum. On the miniature speakers, Bob's vocal sat well in the mix, but during the mastering session I realized Bob's vocal was not punching through the music on certain songs. So that's one regret I have with Fiction Man - not making Bob's voice a bit louder.

Back to top

|

Bubble (2005)

The 6-track EP Bubble was meant to feature songs used on the soundtrack for Steven Soderbergh's minimalist film of the same title set in Ohio. Apart from Bob's acoustic songs, we also recorded a couple of "full band" songs with vocals including 'All Men Are Freezing' and '747 Ego' - a song that was originally planned to be included in a bar scene in the film. In the end Mr. Soderbergh chose to use only Bob's acoustic pieces in the soundtrack. In any case, it was a thrill to take some small part in a project like this.

Back to top

|

From A Compound Eye (2006)

Unlike all the other albums I made with Bob, From A Compound Eye was the only one we made together side by side in the studio from beginning to end. We did this one in the summer of 2005. I may be wrong about this, but I believe it took us 11 days to track and mix all 26 songs.

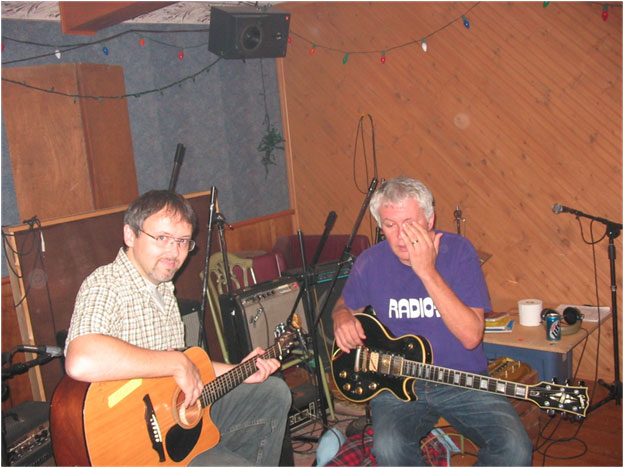

It was customary for Bob to have a lot of visitors in the studio during the Guided By Voices sessions. But this time Bob had the bare minimum of friends and family dropping in. Among those who sat in for a day were Bob's brother Jim on guitar and Chris Sheehan on piano, both performing on the song 'Gold.' Chris Sheehan also added piano to 'US Mustard Company.' Bob's wife Sarah, who was staying with Bob at a nearby hotel in Kent (home of Kent State University), also dropped by now and then, sometimes to feed us. The result of having few people around was a tension-free recording session in a relaxed environment.

While working on Fiction Man, there were sometimes risky decisions and things got musically exotic, but Bob seemed to dig that. By the time we got to F.A.C.E., Bob was very much into adding in those exotic elements. For better or worse, on this album my trepidation was gone when it came to the musical accompaniment. Today I look back and think some of those extra noises should have been dropped. In Circus Devils it was standard procedure for me to get happy with all the sounds. On Bob's later solo albums I would become much more reserved.

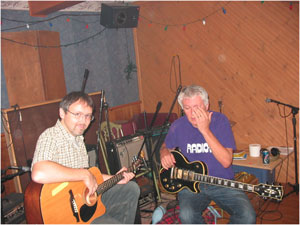

We recorded the album at Waterloo Sound on the ground floor of Scott Bennett's house situated in a fairly quiet residential neighborhood about one mile from the University. The house's unassuming appearance offered no clue as to what went on inside. Scott was usually around and ready to take over as engineer in the control room if I was busy drumming or performing overdubs. He also stepped in as a performer on three songs: 'Gold' (harmonica), 'I'm a Widow' (guitar solo) and Conqueror Of The Moon' (whistling). Scott's whistling was especially appreciated because Bob and I were both no good at it.

2005 - Waterloo Sound, Kent Ohio (aka: Scott Bennet's house)

(photo by Sjors de Vries)

With Scott Bennett at Waterloo Sound (Scott is the tall guy on the left)

(photo by Chris Sheehen)

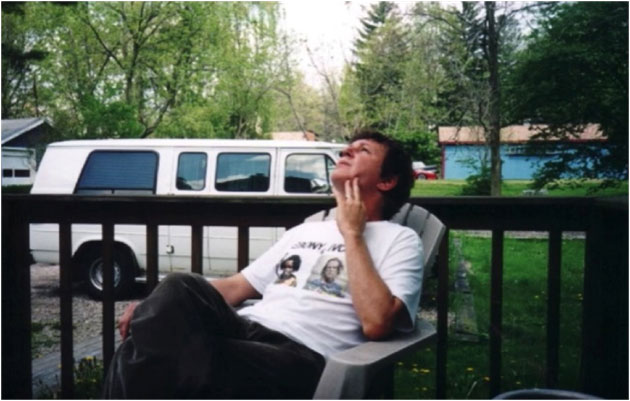

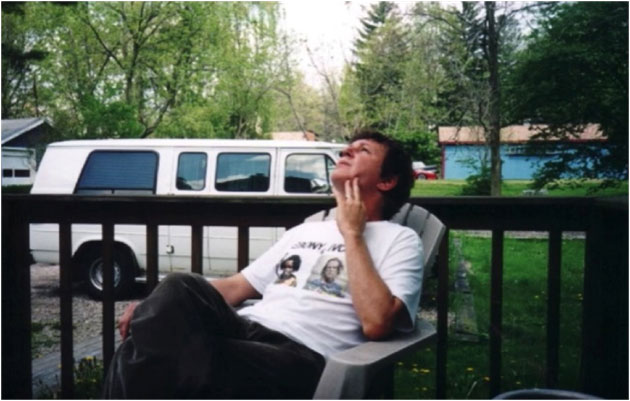

Bob taking a break on the back deck at Waterloo Sound during the FACE sessions

(photo by Scott Bennett)

Whenever we took a break from recording, the house seemed eerily quiet - a sharp contrast to the constant laughter and raucous banter from band members, friends and onlookers during the recording of GBV's Half Smiles Of The Decomposed, which we recorded there a year or two before. While tracking overdubs for F.A.C.E. there was no need to send a messenger into the hang-out room to tell the gang to keep the noise down because the hang-out room was empty. Bob knew I wasn't one for hanging out and drinking, so the picture we presented to anyone who peeked in did not resemble the customary party scene with rooms packed with men (only men) along with piles of empty beer bottles. Getting down to work and keeping our focus sharp was fine by Bob, who I believe appreciated the change of atmosphere, at least for this particular project.

I use the word work, but with Bob present from the first drum count-off to the final fader dip on the final mix, it didn't feel much like work to me. We seemed to fall into a zone where making a record was second nature. We never slacked off, but at the same time there was an almost effortless flow to the recording process that I hadn't experienced before and haven't since. Things just came together painlessly, without a hitch.

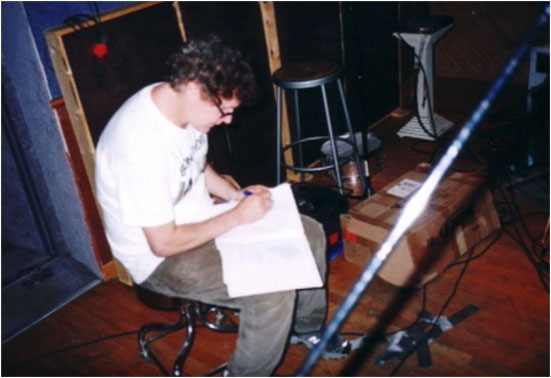

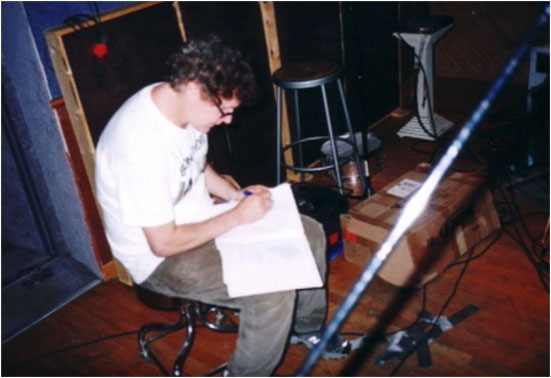

Bob revising his lyrics

(photo by Scott Bennett)

Bob's songwriting was expansive, playful and free, with wide swings from power pop to pretty and gentle to deep, dark and shadowy. Bob's doctrine of "the four Ps" was on display here (pop, punk, prog and psychedelic). Taking my cue from the songs and Bob's tireless energy, I didn't really have the chance to hold back and be cautious. Caution would come later, after I began to work alone again on Bob's later albums. With Bob in the studio I was able to get an instant thumbs up for any and all ideas that came up, including ideas I would not have entertained had I been working alone. To give an example, take the song 'The Right Thing.'

We had a toy whirling drum that I decided to use as a rhythm keeper for 'The Right Thing.' The fact that I had an idea of this kind was the result of the free and open "anything goes" atmosphere. I recorded a few bars with the toy drum and made a loop with it, dropping the pitch of the drum in the process to make it sound less like a toy. Bob and I then played guitar and drums overtop of the loop. In the end, the toy drum became the rhythmic driver of the song. Then came the decision about what to put on the ending of the song. Should it be a guitar solo? A bit of keyboard noodling? "Wait, how about a Jew's harp solo?" Once again, Bob gave the thumbs up. A Jew's harp solo was something I would never again venture, and for good reason. Decisions like this were made with a clear head, without the aid of smokes or special baked goods.

Whenever I second-guessed what I was doing, Bob was there to give the green light. In general we practiced the "Fuck yea, let's try it" school of music production, which can be dangerous. I think what made it safe for us was the fact that we were working squarely in the service of the songs alone. Had we been working in the service of some abstract idea about how the record should sound by struggling to emulate the sound of other records we admired, or else followed the lead of ego by fancying ourselves pioneering recording artists in the throes of great art, then I would have gotten hopelessly lost and the recording would have stretched on for weeks.

I had no trademark production style to put on display, and no bounds to observe as a performer. As a one-man band I was Bob's hired hand. I was not playing for myself. The songs and the show were Bob's. I wasn't there to play Phil Spector and pretend to matter, at least insofar as Bob's fans were concerned. The challenge (or struggle), was to find out what each song was asking for. That's why an album like F.A.C.E. has such a wide range of treatments going on. Every song asks for different things, so the idea is to tune into that silent request. If we made a mistake on F.A.C.E., it was to give a song more than what it asked for. Some songs asked for very little and needed very little, but as I keep saying, I sometimes got carried away with accompaniment and added too much. Whether there were 24 tracks available, or only 8 tracks (as in the case of Fiction Man), it made little difference when it came to my appetite for stuffing the songs with more textures and flavors.

Working by myself on future albums, I often gave in to the temptation to err on the side of caution when it came to the music for fear of ruining a song by being musically cute or clever. This kind of cautious, mindfully careful work can make for a solid record, but not always an interesting record or a record with character. On From A Compound Eye, the musical conservatism I'm sometimes guilty of (apart from Circus Devils and Psycho and The Birds), was put aside. Considering it was a double album, I'm surprised we didn't get caught on any snags of the kind I always encounter while working alone.

On most every album there seems to be at least one song that fails to cooperate. Sometimes two or three. What that "problem song" needed to make it come together always remained elusive. In the end it was always something simple that I stumbled upon. Strangely, on F.A.C.E. there was no problem song and no straining or hammering away to get something right. We just dove in and put it together without a fuss. These days I have a more critical ear than I did back then. But for every time I wince at some unfortunate production decision I hear on F.A.C.E. there are three other moments that bring a smile.

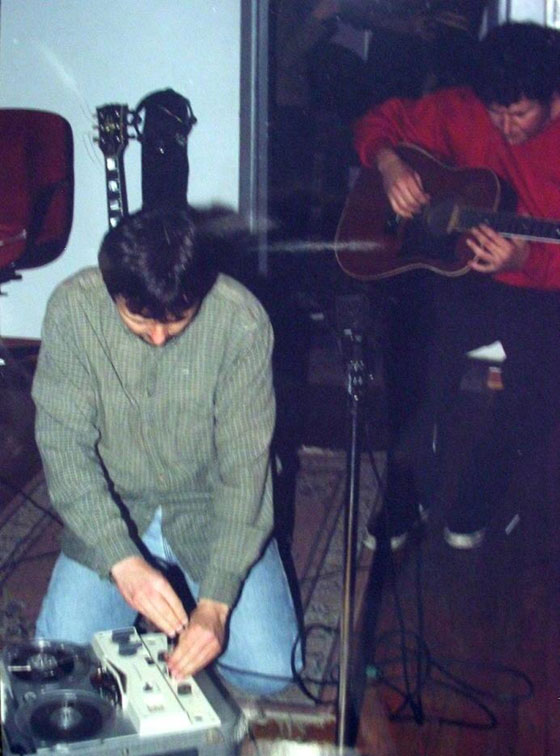

Memory snapshots that come to mind from the FACE session include Bob sitting on the deck at the back of the house going over his song lyrics. As seen in the photo below I clearly remember Bob performing 'Cock Of The Ranbow,' - playing guitar and singing along with the birds and car noise in the background, all captured on tape.

Bob performing 'Cock Of The Rainbow'

(photo by Scott Bennett)

The Dobro you see Bob playing in the photo belonged to Scott Bennet's girlfriend at the time. While Bob sang the song, I messed with my Webcor portable tape machine - the ancient 1950's-made, temperamental, single-track (mono), tube-driven machine used for drums on Fiction Man. You can see the Webcor on the back cover of F.A.C.E. near the bottom. It was first used on Universal Truths and Cycles (2002), on the songs 'Father Sgt. Christmas Card' (on the outro) and on the intro to 'Skin Parade' ("For Christ Sakes Charlie ..."). On this album I also used it to record 'Cock Of The Rainbow' and 'Kensington Cradle.'

A moment not caught on camera (as far as I know) shows Bob's wife Sarah emerging onto the deck during a break to bring us a great meal she'd prepared upstairs in Scott's kitchen. Mostly I just remember seeing Bob in a sustained state of relaxation, sharp focus and contentment. His conversation hinted at a new stage in his musical life. It was time for him to just be Robert Pollard for a while.

I could tell that Bob believed the record was coming together nicely. He was high on the material and pleased with the execution of the songs as we moved along, including all the extra tinkering with keyboards and percussion.

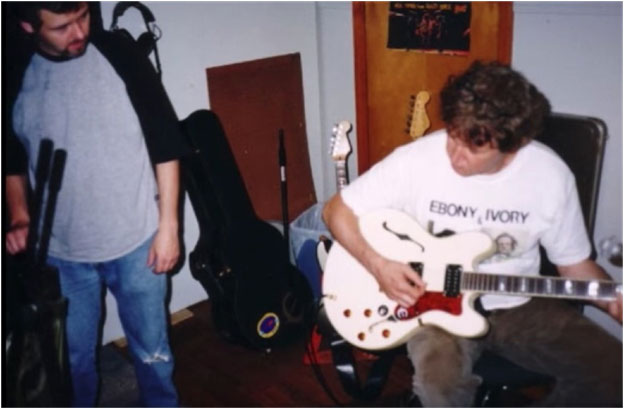

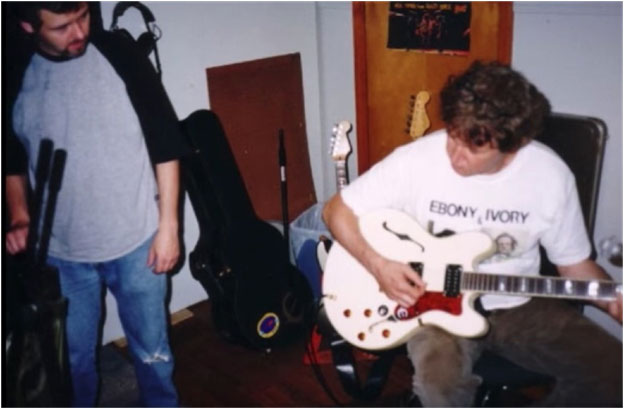

Getting ready to record the basic tracks

(photo by Scott Bennett)

We began the session by laying down basic tracks for each song - Bob on guitar and me on drums. Bob also sang a scratch vocal to help with timing changes. On most of the later albums I made with Bob, the first thing we did in the studio was to lay down the main rhythm guitar track without drums (with Bob on guitar). On a few of the albums where I did the main guitar myself, I would replicate the part as heard on Bob's demo recordings. Once the guitar was laid down, I'd move on to the drums, extra guitars, keys and so on.

On F.A.C.E., with Bob and I playing guitar and drums together, each song found its shape and energy right off the bat. This is something difficult to achieve when playing and recording alone, either on drums or guitar. We needed that exchange of energy between us to make the tracks come to life. On many songs we did only a single take before moving on to the next song. There were a few tricky drum timings that I flubbed on the first few takes. One song I recall practicing again and again was 'I Surround You Naked;' specifically the instrumental intro section with the staggered guitar chords. When I first heard the rhythm of those guitar chords as Bob played them on his demo, it wasn't obvious to me how I should approach the drums. This time it actually paid off to sit down and think about rock and roll - something I'd never done before. I also recall needing some extra think-time to nail down the changes in 'Conqueror Of The Moon.'

Once the solid foundations of guitar/drums were laid down, the next step was adding to the color palette on the friendly and pretty songs (ie: US Mustard Company), and adding shadows and shade to the darker songs (ie: 'Other Dogs Remain'). On a song like 'Love Is Stronger Than Witchcraft,' you have both light and shade in play, with light winning out in the end. The rockers needed no further dressing up apart from an extra guitar. Then there were the "romps": '50-Year Old Baby,' 'Field Jacket Blues' and 'Denied,' where Bob gave me the green light to indulge in the same sort of noisy fun found on a Circus Devils album.

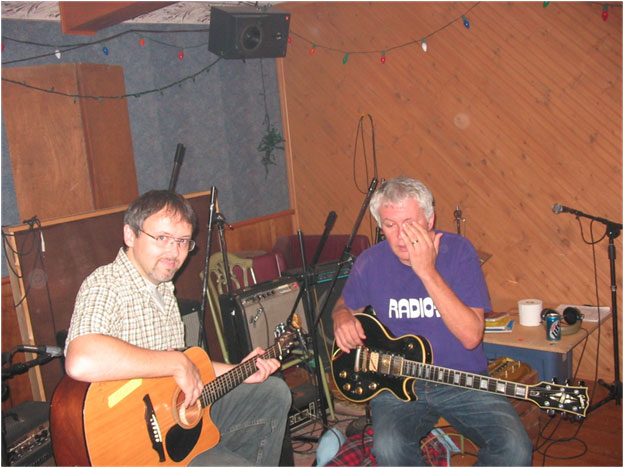

Bob plays the main rhythm guitar you hear on every song. He used a variety of guitars including my Les Paul and Scott's Epiphone hollow body (as seen in the photo above). Bob brought in a guitar or two as well, including a Gibson SG if I recall.

(photo by Scott Bennett)

Performing in the same room with Bob made me a better drummer. I doubt I could have fallen into the pocket on songs like 'I'm a Widow' and 'Hammer In Your Eyes' without Bob there to interact with musically.

I lack confidence as a drummer even though it was my first instrument as a kid. While making records I often wished I had Kevin March or Jim McPherson on hand to take over on drums. Then there was the fact that I never got around to buying a quality drum set. I can't say that my drumming (or my drums) ever ruined a track outright, but that's less than high praise for any musician.

On 'The Numbered Head' Bob wanted to go off into a musical side journey - a prospect that made me nervous as a drummer. I don't do jamming. Maybe it's because I'm not a good enough musician to jam, or because I can't trust myself once I go off script. But more than that, I just don't find jamming interesting as a listener. It makes me impatient and ansty. My solution on 'The Numbered Head' was to employ what I called the "Shoe in the clothes dryer" drum technique, and keep up with the oddly syncopated fills, taking inspiration directly from Ringo.

(photo by Scott Bennett)

As a guitar player, my role was to be the Harrison to Bob's Lennon and add non-intrusive, nuanced plucking parts or counter-melodies that were intended to enrich the harmonic picture (See 'Payment For The Babies' or the ending of 'US Mustard Company'). On 'Blessed In An Open Head' and on the ending of 'Recovering,' Bob added his own guitar accompaniment, hitting the spot in a way that I wasn't able to.

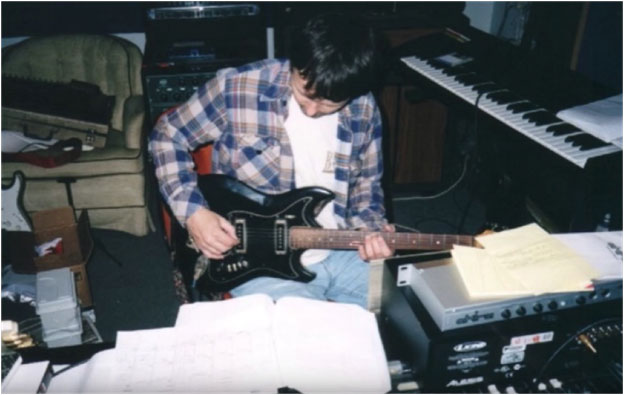

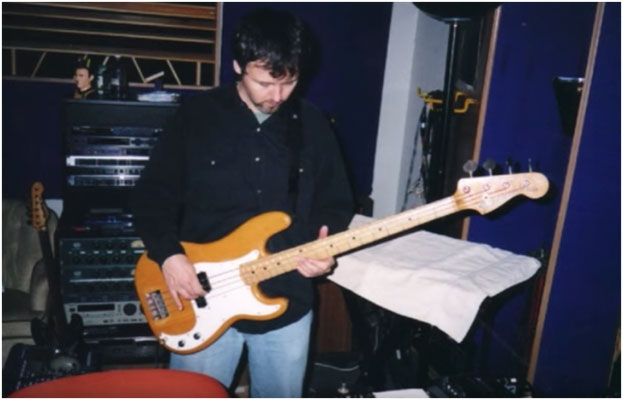

In these photos you see me behind my small-scale,1960s-era Starlight Japanese drum kit supplemented with a Ludwig snare. Also in service are my black Hagstrom guitar, also from the 60s, and my mid-70s Fender Precision bass.

The keyboard is the one thing I might have toned down in hindsight. On 'Blessed In An Open Head,' I was able to avoid the danger of keyboard overload by removing the keyboard part entirely and having Bob sing the part wordlessly instead (it's the repeated melodic phrase running through the verses).

(photo by Scott Bennett)

Bass guitar is the instrument I'm most confident with, and brings me the most pleasure as the element that glues things together and makes things complete. For that reason, I saved putting on bass for last in order to have the satisfaction of finally hearing the songs come together and shake the air the way they're supposed to.

The one song where we veered off script for an hour or so was 'Kensington Cradle' - the runt of the litter. This was an experiment done for a laugh on the Webcor tape machine. I suspect that most listeners to the F.A.C.E. album will skip over this song when it comes up. I feel free to say this because I share a writing credit.

Messing with the Webcor mono tape deck

(photo by Scott Bennett)

Careful listening at the mixing desk

(photo by Scott Bennett)

Following the obligatory listen to all the finished mixes turned up loud in Bob's car (parked at the back of the house), there wasn't much to say except, "We did good, huh?" Once the whole album was assembled, I was struck by the wide scope of moods, from wistful to defiant to friendly to introspective to playful to dramatic. Bob had good reason to feel proud. The sound of the album is gauzy and warm, due to it being 100% analog. The sound may lack clarity but the warm texture seems to fit nicely with this batch of songs. My personal favorites on F.A.C.E. are probably considered supporting tracks to the more popular songs. They include 'Light Show,' 'Payment For The Babies,' 'Blessed In An Open Head, 'Fresh Threats, Salad Shooters and Zip Guns,' 'Hammer In Your Eyes' 'Kick Me And Cancel,' and 'Other Dogs Remain.'

Over the years I had an intense but fleeting relationship with many of Bob's songs. I'm grateful that he was pleased by my contribution and honored that he put his trust in me. Once in a while someone will remind me of a particular album - usually Coast To Coast Carpet Of Love - and say something kind, reminding me that it's ok for me to feel proud of the work as well.

Bob's future solo projects seemed to take off from the foundation laid down by F.A.C.E. They include the introspective, sometimes dramatic and serious moods on Silverfish Trivia, The Crawling Distance and Moses On A Snail. Then there's the friendly, self-assured, outgoing atmosphere of Coast To Coast Carpet Of Love and We All Got Out Of The Army. Then there are the playfully eccentric moods on Standard Gargoyle Decisions, Elephant Jokes and Space City Kicks. There's also the joyful delirium of We've Moved by Psycho and The Birds. All of these moods can be found on From A Compound Eye; an album that brings many good memories.

Back to top

|

Normal Happiness (2006)

The demos for Normal Happiness (originally titled Gasoline Ragtime) did not sound to me like a continuation of From A Compound Eye. Bob's songwriting on F.A.C.E was big and expansive, so I tried to give that album a big sound. The songs this time were more inwardly focused and intimate, so I decided to try for a tighter sound in a smaller space by putting the drum set in a storage closet. With some blankets draped on the walls for sound dampening, it helped to give the drums a tighter, punchier sound.

This was the final all-analog Robert Pollard solo album that I produced. It was recorded on the Sony MCI 2-inch tape machine at Waterloo Sound - the same machine we used for most of Half Smiles Of The Decomposed and F.A.C.E. That tape machine gave the album its warm and wooly sound.

The Normal Happiness session was also the last time Bob and I played all the basic tracks together (drums and rhythm guitar). It's always important to undergird each song with the right energy. Playing together with Bob made that much easier. On hyper-kinetic songs like 'Accidental Texas Who,' and 'Full Sun (Dig The Slowness)' having Bob there playing along on guitar had a liberating effect for me and made the drumming fun and easy. By the way, Bob did not have to squeeze into the closet with me and the drum set. We kept an eye on each other through an open doorway while we played.

The task I set for myself on this album was to apply guitar layering for harmonic richness and/or to enhance a song's emotional affect. A fortunate example of this is the fluid plucked guitar part in Boxing About.

The Waterloo Sound control room in 2006

(photo by Todd Tobias)

Bob tracking with an SG

(photo by Scott Bennett)

Bob doing a vocal take with a hand-held mic - in this case a Shure SM48.

(photo by Scott Bennett)

At the mic stand with the Audio Technica condenser mic and pop-screen.

The SM48 you see here was used as a talk-back mic.

(photo by Scott Bennett)

Between about 2003 and 2009 we had a wonderful piece of equipment at Waterloo Sound - a monstrous handmade, tube compressor unit built by a guy I will call Keith, who allowed Scott Bennett to park the compressor at the studio in exchange for studio time. A few of the albums which benefited from the compressor were Half Smiles of the Decomposed, F.A.C.E., Normal Happiness, Sgt. Disco, Ataxia, Coast To Coast Carpet of Love, Standard Gargoyle Decisions, Silverfish Trivia and Gringo. Keith was an electronics wizard and gifted sound engineer. Sadly, he also had an addiction to heroin. To support his habit, he rented out his handmade compressor units to big name producers, including the guy who produced Mariah Carey.

For those among you who are not sound engineers, a compressor squeezes the dynamics of a sound (makes the soft parts louder and the loud parts softer). When applied to vocals, it helps to normalize the volume of the voice - and when applied to instruments, it gives the sound a certain punch and presence. On Normal Happiness, the guitars and vocal benefited a lot from Keith's compressor.

For a long while Keith seemed to have disappeared, and he'd left behind this amazing compressor at the studio. Naturally I continued to use it. At some point a few years later Keith got in touch and asked me to return his gear - a sad day for me. When I delivered the compressor to his house, Keith yelled at me from behind his closed door.

"Who the fuck are you?!"

"It's Todd," I answered.

"Todd who?" he snapped. "I've got a gun!"

I should have run away and kept the compressor, but instead I gently reminded Keith why I was there.

"What the fuck do you want?" he yelled, interrupting me. "I've got a gun!" he repeated.

Finally, Keith opened the door. Instead of a gun he was holding a huge, heaping bowl of Count Chocula, or maybe it was Cocoa Krispies. Anyway, it was one of those brown, sugary cereals I used to eat when I was a kid. The bowl was not cereal-sized, but one of those big mixing bowls used for cake batter. Keith looked terrible, with gray skin and deeply sunk-in eyes. When he spotted his big compressor sitting on the porch he finally settled down. I decided not to accept his invitation when he asked me to step inside. After that odd encounter I keenly felt the compressor's absence at the studio and wondered whatever became of it. Maybe it showed up on recordings by Coldplay or Justin Bieber. It was a great help on plenty of our projects. So I offer a belated "thank you" to Keith, wherever he may be.

Keith's magical hand-made tube gear

(photo by Todd Tobias)

One thing I remember about Keith was his conventional musical tastes. Once when he stopped in at the studio, I was busy mixing something from the Standard Gargoyle Decisions album. He stopped to listen, cocked his head, then looked at me and shook his head, as if to say "What the fuck is that shit?" There was a look of pity on his face.

I don't imagine Normal Happiness is an album that clicks with listeners right away on account of the mix-up of moods and styles and the impression that the party is private - this in contrast to F.A.C.E., on which Bob seems to be singing directly to everyone. This is just my own impression.

There are exuberant, high energy songs ('Accidental Texas Who,' 'Supernatural Car Lover,' 'Full Sun (Dig The Slowness)'), pretty, wistful songs ('Boxing About,' 'I Feel Gone Again'), loony songs ('Gasoline Ragtime,' 'Whispering Whip'), pop songs ('Rhoda Rhoda,' 'Get a Faceful') and dark songs ('Give Up The Grape,' 'Pegasus Glue Factory') and then there is 'Serious Bird Woman.'

I'd like to know where 'Serious Bird Woman' comes from. I didn't ask. At first, I thought the tortured longing in Bob's vocal was an ironic put on, but then I began to suspect that it wasn't. The decision to take it as 100% honest and heartfelt made my musical approach simpler. Playing it straight, I used shifting guitar chords meant to accentuate the sad longing in Bob's voice. I still find something oddly uncomfortable about 'Serious Bird Woman.' For some reason I had Bob stand across the room from the microphone when he sang this one. That's what accounts for the odd vocal sound. I think this approach to the vocals was also taken on 'Towers and Landslides.'

Once again, Chris Sheehan makes an appearance, adding an exciting synthesizer at the tail end of 'Full Sun (Dig the Slowness)', and putting a nice touch on the closing of the album.

Back to top

|

Coast To Coast Carpet Of Love (2007)

I don't know if it's common knowledge, but the songs on the albums Coast to Coast Carpet of Love and Standard Gargoyle Decisions were all written for the same heaping double album set to be called Coast to Coast Carpet Of Blood.

I remember Bob handing over the demo collection for the ambitious double album set to be the follow up to 'Normal Happiness.' This was an exciting group of songs, but as a complete album, I noticed a schizophrenic mood. In one camp were the friendly songs and in the other camp, the more challenging, playfully eccentric and darker songs. The line between the two groups was easily drawn, without much overlap. As I began what would become a two-month long recording session (my longest ever), I kept thinking: "This should be two separate albums." While I appreciated Bob's artistic ambition, my thoughts were with the listeners. How could you go from 'Miles Under The Skin' to 'Butcher Man' without feeling jarred?

Many years later, in 2021, Bob decided to create a single album (Our Gaze) by hand-picking songs from both collections originally released as two albums ('Coast to Coast Carpet of Love,' and 'Standard Gargoyle Decisions'). So in the end, the issue was not in having a mixture of different moods, but rather in the sheer volume of tracks. By cutting it down to a single LP, the interplay of moods worked much better.

I believe as a double album, From A Compound Eye had been a big, bold statement for Bob, casting a bright light that would be difficult to outshine. Whatever had made that group of songs flow from one to the other in an effortless way was absent on the newly planned double album. I could tell as much by listening to the demos in random order. However, when Bob picked out the friendly songs and put them all together into a single album collection, suddenly the thing lit up and came to life as Coast To Coast Carpet Of Love.

The remaining half of the former double album then became Standard Gargoyle Decisions. As with its lighter twin, a distinct personality and identity emerged when these songs were bunched together. A favorite of mine in this collection is the spaced out 'The Island Lobby.'

Even before the double album idea was dropped, I decided to segregate the songs and record them in two separate groups. My dividing line pretty much reflected Bob's when it came time to split the double album in two, with just a couple of exceptions ('Folded Claws' and 'Penumbra'). 'Penumbra' was recorded along with what would become the Standard Gargoyle set. And 'Folded Claws' was bunched in with the set of friendly songs. When I think of 'Folded Claws' as part of Standard Gargoyle Decisions and 'Penumbra' appearing on Coast To Coast Carpet Of Love, I think of the Yin Yang symbol, where you see the two opposing halves - one dark and one light, but within each half is a small piece of its opposite. Maybe this was Bob's way of reminding us that these two albums were once a single creature before being broken in two.

I'd like to remind everyone of the astonishing act of faith on Bob's part in putting his songs into my hands. He wasn't even popping in to check up on my progress. It's hard to imagine the levels of anticipation he suffered through while I was working. He told me a few times that receiving the finished work was like being a kid on Christmas morning. There are people who might think it's impossible to ruin a good Bob Pollard song. I can see why someone would think so, but I can tell you that when I took a wrong turn with a song, ruining it was a real possibility. I like to think that I was always able to catch myself and make the correction. Nobody has heard those aborted versions because they were destroyed. I could use the word 'deleted' here instead of destroyed, but no. They were destroyed.

The work began with me studying Bob's demos and learning Bob's guitar parts. Once I put the main guitar parts down, they served as the foundation for each song. In other words, I carried on by playing the drums, following along with the guitar tracks. In effect, I was pretending to be a band, doing my best to play off the energy of that other "me" who played whatever other instruments I was not playing at the time. Once the drums were down, layering on new instruments became less troublesome thanks to the timekeeping.

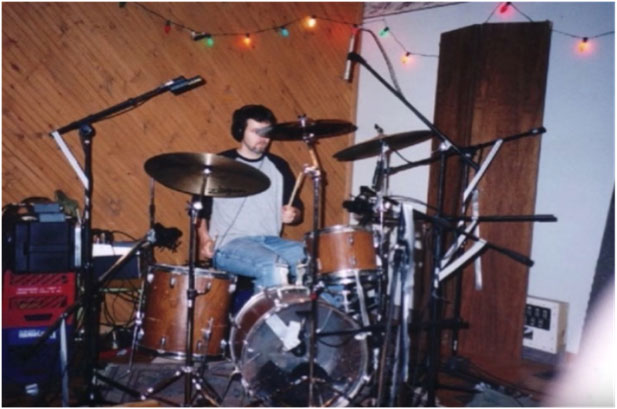

Drumming on Coast to Coast Carpet of Love / Standard Gargoyle Decisions

(photo by Scott Bennett)

Sometimes I had to call Bob and ask how he played a particular passage on the guitar demo. I may have found the right notes on the guitar neck, but sometimes I was playing it on the wrong string, which gave it a different sonic character. I learned that Bob likes to focus on the lower (deeper pitched) strings of the guitar. He also has a unique, aggressive way of attacking the strings with a guitar pick. Sometimes I tried to emulate that forceful way of playing. It helped me while figuring out the guitar parts to know that Bob does not use alternate tunings. By contrast, when writing material for Circus Devils I rarely used standard tuning. Bob's "correct" tuning helped to make things simpler. But even though Bob did not mess with the tuning, sometimes the pitch on his strings had drifted off the mark. I would then re-tune my guitar to match Bob's. In other words, an F chord on Bob's demo might be closer to an E chord on the piano, but only because the tuning had drifted on Bob's low E string, which he then used to tune the rest of his strings. I suspect this would only be of interest to fellow musicians, and maybe not even then.

A good deal of time was spent figuring out secondary guitar parts, added in to broaden the harmonic picture, while at the same time being careful not to hijack the song and take it to a foreign place. As always, the bass guitar - the glue that binds it all together - was added in last.

My assignment - or the assignment I gave to myself - was to realize the music without calling attention to myself as a performer. This had not been my approach on Fiction Man, where I let myself off the leash.

My role on Coast To Coast Carpet Of Love was to be a tailor, and not a fairy godmother. A good tailor is invisible. You can admire a nicely fitting suit without having to think about the work that went into making it. I wasn't there to pretty up the songs in the way a producer of mainstream pop would do, by putting a sonic stamp on the record. The songs were great - always a good starting point. In my view a naturalistic treatment was all they needed, with the sounds of real (non-electronic) strings and membranes vibrating the air. There was no need to gussy things up, and besides, I didn't have the skill or the tools or the know-how to make a mainstream-sounding pop record. Staying clear of keyboards was one thing I decided early on. 'When We Were Slaves' was an exception. But I still had to dress up each song using the customary tools (guitars and drums). I wanted the listeners to hear a song and not think about things like the drums and bass or the "band" that played them. The thing was to preserve an illusion that the songs were something organic that grew up out of the fertile ground of Bob's imagination already fully formed - as if they had jumped straight from Bob's head onto the record. Anyway, that was the assignment.

The one song in this set that proved difficult - and there is almost always at least one - was 'Slow Hamilton.' This song required three or four versions before I got it right. I kept thinking, "Part C needs to be prettier." This is the part with the lyric; "A life beyond slow Hamilton's scheduled day." That particular section needed heightening and broadening, but at first the missing element would not show itself. Attempts at prettying it up with keyboards sounded painfully forced and out of place. At last I fell into a silky guitar part that glued things together nicely and helped the song lift off the ground where it needed to go.

Work on the set of weirder songs comprising Standard Gargoyle Decisions would be more comfortable for me. Not easier, just less fraught with danger, which may seem counterintuitive. With these meaner songs, instead of being a tailor, I was more like Dr. Frankenstein - assembling the bones and organs and hoping that a living creature would be the result - and not just a heap of dead body parts.

Realizing a friendly (more conventional) song meant approximating what was in my head in terms of instrumentation and treatments. Things had to be glued down tight with the proper drumbeats and all the notes on the supporting instruments had to be just right - as in "there is no other note that works but the right one."

However, with the weirder songs in this set, I had nothing fixed in my mind before I began. Instead of getting things "right" I was just feeling my way through as I went, with the hope of discovering the finished song instead of seeking to establish something already mapped out in my head. This made recording the darker and weirder songs more enjoyable. I think that's why I saved them for last.

When everything was done, I felt the treatments on the Coast To Coast album were too simple, maybe even boring and predictable - especially in light of the more adventurous work on Standard Gargoyle Decisions. Bob reassured me that I'd done well. But it's taken years for me to get past my doubts. Now I can listen back to it and feel pleased with everything going on in Coast To Coast Carpet Of Love. In the end, I believe a gentle touch was the right touch.

The lonely marathon recording session at Waterloo Sound that produced these two albums went one step farther in terms of my energy investment than anything I'd done before. I felt challenged and privileged to be building these albums, working from Bob's set of blueprints. But then I was also happy to go home and leave the construction behind. There was a time when I wasn't able to simply listen and enjoy these songs the way others do. It was like having an intense relationship that leaves you exhausted. You just want some distance. But now that several years have gone by, the songs confront me now like old friends.

Back to top

|

Standard Gargoyle Decisions (2007)

This is an album where Bob's "anything goes" approach to songwriting is on display. Some of the songs have the quality of being born in a dream ('Pill Gone Girl,' 'Hero Blows the Revolution,' and 'Butcher Man' come to mind). Songs like these seem more like spontaneous eruptions than compositions.

I feel I could have done even more to accentuate the weird/ mean/ funny/ scary qualities in these songs, especially on the songs with a tossed-off quality. It was a case of holding back out of uncertainty in the mixing stage because I was working alone. If Bob had been in the studio with me, he might have given the green light to any number of eccentric touches that I decided to cut. In the back of my mind, there is always a voice warning me, saying "Don't get too cute."

This was the sort of album that invited messing around. There is never any harm in adding extraneous stuff in the tracking stage. But when it came time to mix, I wanted to make sure the songs shone through without the cute distractions. It was a Robert Pollard record, not a Circus Devils record, so I exercised caution. An analogy to this would be shooting a film with inclusion as a guiding principle, and then editing with extreme prejudice.

The demo for 'The Killers' was first recorded by Psycho and The Birds. For this new version I decided to use the same ancient Webcor mono tape deck used on the drum kit for that original version. The intro to 'The Killers' with the whiney voice snippet: "Bob, we gotta - we need to do it this way," coupled with the "Webcor Sound" of the sweetly distorted hi-hat, announced the album as something very distinct from Coast to Coast right from the start.

I remember Rich Turiel being at the vocal tracking session. He and Bob can be heard shouting "Here Comes Garcia!"

'Come Here Beautiful' is simply Bob's demo with some keyboard additions in the style of Psycho and the Birds. It's one of my favorites on the album, along with 'Pill Gone Girl,' 'Motion Sickness Ghosts' and 'The Island Lobby' - a song in which I felt especially at home as a musician.

Back to top

|

Silverfish Trivia (2007)

I remember Silverfish Trivia starting off as a full-length album. But the result did not sit well with Bob. He didn't go into his reasons for breaking up the album, but I guessed either he was unhappy with some of the songs, or else unhappy with my production - or some aspect of my treatment of the songs.

I associate Silverfish Trivia with The Crawling Distance, but on that later album the solemn, downbeat songs were offset by a few playful rockers and a couple of pretty tracks. That sort of wide-swinging dynamic was missing on the original, full-length Silverfish Trivia. Instead of keeping listeners off balance, it kept an even keel throughout. Maybe this was the problem. Anyway, Bob's solution was to keep the best three songs, add in a few quietly unassuming but emotionally affecting tracks to solidify the mood, and make it an EP. The result is a record with a big, low-key personality - if that makes sense? Anyway, it's not the sort of personality Bob is generally known and appreciated for. This might be why Silverfish Trivia and The Crawling Distance remain my two personal favorites among the solo albums I recorded with Bob.

The songs that were cut from the original album became a collection of B-sides, including 'Coast To Coast Carpet Of Love' (the song), 'Piss Along You Bird,' 'Met Her At A Seance,' and 'Street Velocity.' With these songs gone, what remained defines a unique atmosphere, better focused and uncluttered.

The trio of songs: 'Circle Saw Boys Club,' 'Touched to Be Sure' and 'Cats Love a Parade' were too good to share an album with those other tracks, and needed a showcase of their own ... or so I assume Bob's thinking went. With supporting tracks like 'Wickerman Smile' and the cello instrumentals added in, the record contains for me a special warmth and emotional gravity. As Bob's work goes, the atmosphere here is uncharacteristically "heavy." By that I don't mean a heavy rock sound. I mean the sort of heaviness that comes when you create in the service of emotion and the soul. Of course, what passes for "emotional" and "soulful" in popular music is insipid hash next to the richness you hear in songs like 'Circle Saw Boys Club' and 'Touched To Be Sure.' Anyway, I always appreciate the results when Bob goes to these deeper places.

The work by our go-to cellist Chris George on 'Come Outside' was based on Bob's demo - with Chris playing both Bob's guitar part and vocal melody note for note on the cello. In the case of 'Speak of Many Colors,' everything the cellos do here was taken from a recording of two guitars - one Bob's and one mine - with my guitar doing interweaving harmonies on top of Bob's main guitar (taken from the demo). Once again Chris matches everything Bob and I played on the two guitars note for note. Since I don't read or write music, Chris was left on his own to write his charts by listening to the guitar tracks and transcribing every note. It was astonishing to hear the result after I'd gotten used to the all-guitar version. It seemed to put the song into another musical dimension.

Bob at the vocal mic

(photo by Scott Bennett)

The prog odyssey 'Cats Love a Parade' took some planning, first from Bob in its conception, and later on with the recording. After hearing the demo, I knew we would not be recording the entire song in one go. It was the first time we'd recorded a song with movements and recurring themes, and also the last time. The song is like a trip that sets off and ends up in the same place, with the main adventure going on somewhere in between. Bob laid down his main guitars and vocals in 5 separate chunks. From there I had fun piecing it all together. At the very beginning of the track we hear a snippet of audio taken from Bob's DVD player. As Bob explained it, while watching a movie he pushed the forward skip button on his remote, and the audio stayed on. The result is the sound of clipped voices captured on Bob's cassette recorder. He didn't say what the movie or song was, but the snippet sounds to me like 'The Battle Hymn Of The Republic.' The intro, ending and weird middle sections were recorded on my 8-track Fostex ¼-inch tape machine - the same machine used for the recording of Fiction Man and the quiet songs on Universal Truths And Cycles and From A Compound Eye.

For me the intro/ending sections of 'Cats Love a Parade' have the quality of speaking directly to the listener, drawing you closer as if Bob is whispering a secret. Some listeners might recognize bits of the music in the big splashy sections because they first appeared on the Psycho and The Birds EP Check Your Zoo, with Bob using Psycho and the Birds as the farm team. The middle section contains some added color from me in the tradition of Circus Devils. It may not sound like it, but I practiced restraint here.

Taken as a whole, Cats Love A Parade can either be a dizzying, delightful trip or else leave you stranded. I get that some people are turned off by this sort of expansive songwriting, and prefer their songs to be served up in easy to swallow nuggets. But those people can at least admire Bob's ambition here. For me this song is a deep dive into some internal dimension where Bob felt at home, at least during that period of his life when the song was written.

Back to top

|

We've Moved by Psycho And The Birds (2008)

Not a Robert Pollard solo album, but still me working with Bob's songs. The difference here is that Bob's original demos were left in on every song- serving as the foundation for each song over which "the Birds" added their instruments.

In the midst of a very active two-year period of recording (2006-2008), Bob and I completed a mess of albums including From A Compound Eye, Normal Happiness, Coast To Coast Carpet of Love, Standard Gargoyle Decisions, Sgt. Disco, Ataxia, and two full length albums and an EP from Psycho and the Birds (Bob on acoustic guitar and vocal / me on the other stuff).

I understand how Psycho and the Birds might be regarded as a hiccup or tiny footnote in Bob's career, but I'll try my best to make the case for bothering to listen to (and get acquainted with) the band's third and final album We've Moved (2008). It's an album that may require a period of adjustment before the enjoyment arrives.

The first Psycho and the Birds album was a lark, assembled by me taking a collection of Bob's demos and adding in accompaniment directly on top of those rough recordings. This would be our M.O. for the other two P&B albums as well. For the listener it meant some difficulty making out Bob's lyrics above the controlled racket taking place, created by the drums, bass, keyboards and electric guitars, all joyfully added with no thought of reigning in whatever musical impulse took hold. Bob seemed unconcerned with the unavoidable burying of his vocals and me getting happy with all the musical extras. This project was about raw feelings. The lyrics were of secondary importance, which may be another reason Psycho and the Birds has been overlooked (apart from the songs being judged sub-par). I think the songs are great, and recording 'We've' Moved' was the most fun I've ever had as a musician.

Bob's demo process sometimes comes in two stages. First comes the initial run with Bob seated with guitar in front of his recorder (in those days the famous cassette boom box pictured in the chapter on F.A.C.E. and on the cover of Circus Devils' Five), with the melody taking shape inside a mixture of legible phrases and nonsense syllables. From there, stage 2 picks up with Bob taking that first version and honing the melody and writing proper lyrics to carry it. Many of the Psycho and the Birds songs were built upon the foundation of Bob's stage-1 demos before the lyrics were fleshed out. Instead of lamenting this fact, think of it instead as eavesdropping on Bob while he's in the throes of giving birth to a new song and travelling on a self-propelled wave of instant discovery. And he's not alone on the wave. Riding along with Psycho are The Birds, doing their best to keep up.

These are songs that can be enjoyed as pure expressions of the id. As such it's fun to hold on to the illusion that the songs sprang up fully formed with no musicians taking part. Musically, everything you hear on We've Moved is very coherent and locked into place. But at the same time the songs seem to follow some offstage logic or dream logic that's difficult to pin down.

For me as a listener, this tension between what seems composed and what seems improvised all happening at the same time is the source of the album's charm. And along with Bob's vocals, it's a source of the album's humor. Once the songs sink in, the album becomes a joyful experience. Listening to it now, it seems to have the vibe of a backyard party where a strange band performs on the backyard deck - the sort of band where the members are huddled together and hunched over their instruments, having great fun while remaining totally oblivious to the crowd. The band also has a shitty PA system that makes it very hard to understand the singer. But there is an infectious exuberance to the songs that overrides any fear of weirdness, allowing the party to carry on and even to escalate.

Bob would probably describe We've Moved as "ridiculous" - this being a term of endearment for him. On a few of these songs, the unhinged musical accompaniment makes it sound more like "Bird and the Psychos." There are moments of pure delirium on We've Moved, especially if you blast the volume and/or enjoy a smoke before putting it on. But hiding behind the weirdness is a friendly soul born of pure fun. Even casual listeners can enjoy songs like 'I Love A Revolution,' and 'Enon Beach'.

Bob said 'She Tears Out' was among his first attempts at writing a song. I can imagine the 12-year-old Bob cracking himself up while writing the lines "She tears out in her new Jaguar - outta sight - out of this life."

The pretty instrumental 'Poor Old Pine' is the one island of tranquility here, unless you also count 'Tomorrow Man;' a snapshot of deep disconnection or perhaps bemused alienation starring a man (or ghost?) who appears to be watching strangers from his window as they walk down the street. "Walking with socks, shoes ... and feet," he reports, speaking of all the people who pass by - suggesting that he himself does not possess these things. The noises you hear which serve as the sonic setting of 'Tomorrow Man' include a doorstop (the springy kind) being continuously plucked - the way a bored child might pluck it. There is also a tape loop made from a piece of old vinyl - just as the needle is dropped before the first song begins. When I first heard the demo of 'Tomorrow Man,' I asked myself "What is this?" What should I do here? Add in some beatnik jazz? In spite of the cryptic weirdness, the track somehow manages to avoid being scary, and comes off as a breezy interlude before the party atmosphere returns the instant 'Corona Grande' kicks in.

'Corona Grande' sounds to me like a mash-up between early 1970s American Bandstand and a late 1950s Sam Phillips production. Bob's semi-wordless chanting in this song is hilarious to me and kind of astonishing.

There is a moment in the song 'I'm Never Gonna Leave, You're Never Gonna Win,' when Bob is propelled forward by a different sort of wordless chanting - this time more primitive and desperate. I hadn't heard something like that from Bob before and it surprised me when I first put on the demo. I don't even know how to use the alphabet to approximate the sounds he made.

There are echoes from party bands of the early 1960s. Then there are shifts to the early 1980s and a punk vibe. Mixed in-between are song styles that might have been but never were. For example, remember the "mouth trumpet" craze from 1971?... Probably not because it never happened (see track 10: 'Hound Has The Advantage'). Taken as a whole, the album is like a dream taking shape in rock and roll's collective unconscious (ie: Bob's unconscious).

Back to top

|

Robert Pollard Is Off To Business (2008)

Looking back, I'm surprised at how each of the albums I made with Bob have their own distinct flavor. This includes the four GBV albums and everything we did in Circus Devils and Psycho and the Birds. All together it came to about 38 albums in all. What set Off To Business apart was Bob's tightly focused, carefully composed songwriting. I could tell Bob had put a lot of preparation into the construction of these songs. Some of them had an almost austere quality.

On an album like this where I served as a one-man band, the customary feeling leading up to the recording was butterflies in the stomach brought on by the new challenge. But as I prepared to record Off To Business, I felt scared. While studying Bob's demos, some of the songs began to feel weirdly oppressive and claustrophobic. I wasn't able to explain it because it never happened before, and after this album it never happened again.

The songs that worried me were tracks 1 through 4 (The Original Heart, The Blondes, One Years Old, Gratification To Concrete) and track 10 (Wealth And Hell Being). The more I dove into these 5 songs in the planning stage, the more pushy and exacting they seemed. I latched on to the idea that there was only one way of getting these songs right - which meant there were a thousand ways of getting them wrong. Once that idea took hold, it guaranteed a rough time for me. Working alone also made it easy to fall prey to my own insecurity. I've written before about the weirdness of making records alone. As I've mentioned, to an outside observer, this method of record-making might even seem a little bit mad. Sometimes it's important to have someone else there to tell you, "Things are fine, quit belly aching." Likewise, it's good to have someone around to tell you, "Come on, that was crap."

I decided to delay my discomfort and begin with the songs I knew I'd enjoy working on best. I especially enjoyed playing 'To the Path!' and 'Confessions Of A Teenage Jerk-off'. 'Western Centipede,' 'No One But I' and 'Weatherman and Skin Goddess' were also stress-free and enjoyable. These songs were no less polished and carefully composed by Bob, so I have no idea why the other half of the album caused me so much trouble.

As part of my drive to do things "right," I did something I never did before and phoned Bob during a recording session. This happened during the tracking for 'Gratification to Concrete.' Bob and I would discuss an album beforehand in the planning stage or else establish the guitar chords, but I had never called to bother him during the process of recording and mixing an album, partly because I knew he enjoyed the surprise and excitement of receiving the music fully cooked and ready for the vocals to be added, which always came last. The sticking point on 'Gratification to Concrete' was in the verse section - an empty space in each measure where I wanted to insert a repeating guitar lick.

For about two full days I did nothing but try out different guitar parts until I was ready to smash the guitar. I wasn't used to this kind of trouble, or I might have had the sense to walk away and give myself a breather. When it began to affect my digestion, I finally switched my approach and tried a vocal lick in place of the guitar. I had no plans of using my voice on the finished mix, but I could at least try to use my voice to give shape to something, and then play the same notes I sang on guitar or keyboard later on. After putting the guitar aside, it was a matter of minutes before I came up with something functional - a five-syllable vocal part which I then played on a farfisa organ with distortion and a wah-wah effect. As a hook, it sounded silly and dumb to me, but it fit.

So, I had the missing puzzle piece in place, but every time I listened back to it, I felt pain. It got so bad that I decided to break my own rule and get Bob on the phone. I held the phone up to the studio monitors and had Bob listen to the verse playback. He listened to it, then I put the phone back to my ear. At first there was silence. "Let me hear it again," Bob finally said. "Oh shit," I thought. He heard it again, then he said "Yeah, I think it's okay." It was not a big vote of confidence, but nonetheless came as a huge relief. At that point I didn't care that Bob wasn't thrilled with it. I was just tired of being my own worst enemy and eager to move on.

Now I can look back and say that all of my trouble had its origin in the thought that those five songs had to be "exactly right," whatever that meant. It was a case of exercising head-level thinking over gut-level instinct. If the songs have the quality of being overcooked production-wise, it's because I smothered them with too much attention. What this means from a listener's perspective, I don't have a clue. Probably nothing at all.

A couple things to share about the song "To the Path!" One is taking inspiration from The Who's "Love, Reign O'er Me" with the string layering. And on the ending section, I experimented with different percussion beds to achieve a galloping effect. The percussion I settled on was a "talking drum" loop, which had a subtler effect than simply bashing on the tom toms.

Putting my issues aside, Bob did some amazing singing on this album. What comes to mind are the vocals on 'No One But I,' and the first and middle sections in 'Confessions Of A Teenage Jerk-Off.'

Back to top

|

Weatherman And Skin Goddess (2008)

Weatherman And Skin Goddess contains the song 'Coat Factory Zero' on which I imposed myself to a greater degree than usual. The song begins with ominous rumbling and ends with a lilting sort of plaintive guitar theme. Both of these parts I added in myself, unsure if they would make it onto the finished record. One thing Bob is never keen on is a literal interpretation between song lyrics and musical effects or figures. Using music or sounds to invoke the word 'Factory' in the title was a no-no. I also object to this sort of musical cuteness, but on this song I thought I'd break the rule and come into the song's space from "underground" with the rumble and rhythm of figurative machinery.

Back to top

|

The Crawling Distance (2009)

Somewhere between Silverfish Trivia and The Crawling Distance, Bob seemed to go in and out of songwriting periods where the material was shaded by melancholy and introversion - at least that's what I was hearing. There is a "heaviness" to some of these songs that keep them alive in my imagination - not as catchy things that pop into my head, but more the way memories and dreams rest under the surface.

On songs like "It's Easy,' 'No Island,' 'Red Cross Vegas Night' and 'On Shortwave,' Bob appears to be deep diving into his subjects in a way that leaves us behind and at the same time offers us a warm invitation. There is a hint here of some emotional depth and sophistication that I can't fathom, but at the same time I can feel and intuit what's going on. As always, I was tempted to find out from Bob exactly what he was getting at with his lyrics but I always held back from asking, judging it disrespectful.

Even though I had the responsibility of recording the music for The Crawling Distance, the nature of the songs made me wary of imposing myself as a musician. Bob had asked me to keep the rhythm section sparse and dry on a few of the songs, using John Lennon's Plastic Ono Band album as a reference point. Holding back was the proper way to approach this album, whereas on many of the playfully eccentric albums that came later (We All Got Out of The Army, Elephant Jokes, Space City Kicks and Mouseman Cloud) I was itching to get into the studio to have fun with the songs as soon as I heard the demos. The Crawling Distance I approached with more reserve and reverence.

On the album's downbeat opener 'Faking My Harlequin' I used a combination of acoustic and electronic percussion - something I also did on 'Coat Factory Zero' From the Weatherman and Skin Goddess EP. The rhythm bed on these two songs was mechanical in its timing, so it allowed for that kind of treatment, though I was wary about doing it.

Bob was conscious of the album getting too solemn, so he threw in a couple of rockers to keep things balanced, including 'Cave Zone,' - a song that confused me because it was so simple, especially lyrics-wise, with the message "Please leave me alone!" I like that Bob narrows down his escape options to three places: China, a South Sea island, or Montrose. While recording Bob's vocals I always enjoyed it when he slipped into his Jerry Lewis (Professor Kelp) voice, as he does here in the non-verbal vocal section.

I think the melody on track 3 ('Red Cross Vegas Night') is one of Bob's prettiest. For once the cello here is not played by Chris George. It was originally intended for Chris to play. But then I made a guide track for Chris using a cello sampled from a classical music recording. To my ears the sampled cello sounded just fine, so I kept it in the song, though it lays down low in the mix.

At the time it was recorded, I overlooked 'The Butler Stands for us All.' To me it sounded like Bob slipping into a comfortable suit, and offered no real challenge for me as a performer. But now when I hear it, I enjoy the comfort zone it offers. I understand now how only Bob could do this song. Imagine any other singer attempting it and it doesn't come off.

There was one intrusive touch I made on The Crawling Distance that I'm proud of. On 'It's Easy,' I decided to insert a repeating interlude where "clouds of confusion" roll in and threaten to swamp the song, before being quickly vanquished the instant Bob gently sings the words "It's easy - easy - easy." To my ears the swell of churning notes added a bit of tension that actually served to accentuate the song's calmness and sense of peace.

One of my favorite Bob rockers is 'By Silence Be Destroyed' - another playful moment (after 'Cave Zone'), allowing us to take a break from the album's gravity. I enjoyed playing the driving rhythm punctuated by sudden hiccups and banging the drumstick on the metal rim of the floor tom. I always laugh when I hear Bob erupt in his righteous voice, "Hey! Don't give me the guilty finger."